By the 1920s the original hospital structure had grown to include six buildings that housed medical and surgical wards, an x-ray area, operating rooms, a dispensary, the nursing school, and a detention ward for contagious diseases. The capacity of the hospital had grown to 100 beds.

Suddenly, in the early morning hours of May 31, 1923, a barking dog ran from room to room alerting all to the blazing fire that had encaptured the hospital. Notes from the hospital’s history provide the detail:

“This fire … was proof of the hospital’s efficiency. At this time the children learned, if they did not already realize, the friendship and generosity of the community. Although the fire destroyed the Administration Building, including offices and officers’ rooms, wards, the pantries, dining rooms and the kitchen, the hospital did not stop its real work for half a day. Not one child’s life was lost due to the realization of the cooperation of the nurses and doctors. It was owing to the generosity of the hospitals all over the city, and to the taxi cabs that carried these children to the welcoming wards of other hospitals where there own nurses cared for them until one week later when the building had been repaired to such an extent that the little patients could be gathered in their own hospital again.”

Plans were immediately undertaken to secure property for a new home for the hospital. The H.K. Porter property on DeSoto Street was selected as the new site. A public fund-raising campaign was held in 1924, and $1.6 million was raised toward the $1,850,000 cost of the new hospital.

The following is recorded in the annual report from that year: “Its work has prospered beyond even beyond the dreams of its founders. It is the peer of any children’s hospital in America, strictly carrying out its avowed object to limit and prevent sickness and mortality among children, to provide them with medical and surgical aid, and to aid in the training of physicians and nurses in the care of sick children and babies. To do this every means known to modern medical and surgical science has been called into being.”

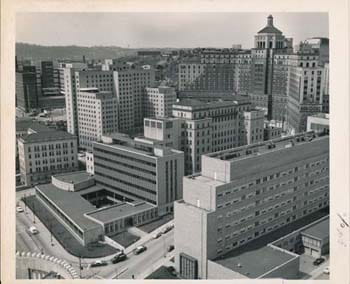

The cornerstone of the new building including a time capsule was laid on October 18, 1925, and the move into the new structure took place on November 1, 1926. With the new beginning, Children’s became the first member of the Medical Center on the campus of the University of Pittsburgh. The hospital became the center for pediatric and orthopaedic training at Pitt. Its wards and clinics became the pediatric training ground for medical students, interns, resident physicians, and student nurses from affiliated schools of nursing. Board minutes explain that “election to the staff automatically elects members to the teaching faculty of the Medical School and these men rank as Professors, Associate Professors, Assistants and Demonstrators.”

The cornerstone of the new building including a time capsule was laid on October 18, 1925, and the move into the new structure took place on November 1, 1926. With the new beginning, Children’s became the first member of the Medical Center on the campus of the University of Pittsburgh. The hospital became the center for pediatric and orthopaedic training at Pitt. Its wards and clinics became the pediatric training ground for medical students, interns, resident physicians, and student nurses from affiliated schools of nursing. Board minutes explain that “election to the staff automatically elects members to the teaching faculty of the Medical School and these men rank as Professors, Associate Professors, Assistants and Demonstrators.”

Throughout the depression Children’s, like all of Pittsburgh, struggled. The years were exceedingly difficult, and a Hospital Maintenance Fund was established to raise money for operating expenses. Through it all, the hospital managed to admit and care for all patients who required hospitalization.

After the Children's Hospital fire, 1923

After the Children's Hospital fire, 1923

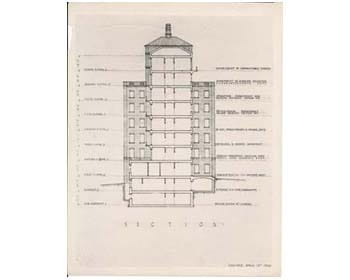

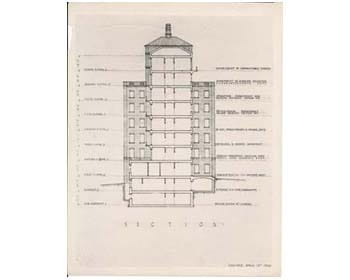

Architectural drawing, 1924

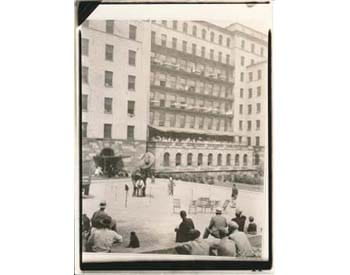

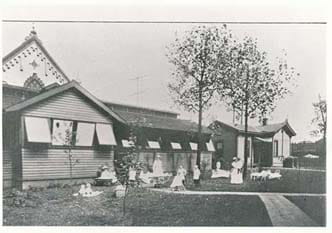

Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, 1926

Moving Day, November 1st, 1926

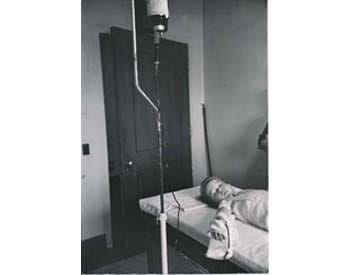

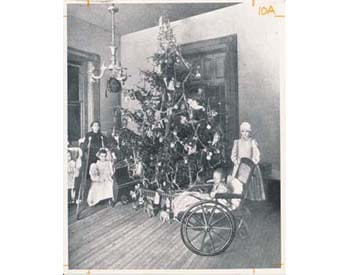

Private room, 1926

Private ward, 1926

Children's Hospital lobby, 1928

The future begins with the past, in the form of a young entrepreneur, Kirk LeMoyne. Master LeMoyne, son of local pediatrician Frank LeMoyne, had an idea. He and his friends decided to raise the necessary $3,000 to endow a single cot at The Western Pennsylvania Hospital. The cot would be used exclusively for babies and children. And in 1887 the Cot Club began its fundraising mission.

The future begins with the past, in the form of a young entrepreneur, Kirk LeMoyne. Master LeMoyne, son of local pediatrician Frank LeMoyne, had an idea. He and his friends decided to raise the necessary $3,000 to endow a single cot at The Western Pennsylvania Hospital. The cot would be used exclusively for babies and children. And in 1887 the Cot Club began its fundraising mission.

The cornerstone of the new building including a time capsule was laid on October 18, 1925, and the move into the new structure took place on November 1, 1926. With the new beginning, Children’s became the first member of the Medical Center on the campus of the University of Pittsburgh. The hospital became the center for pediatric and orthopaedic training at Pitt. Its wards and clinics became the pediatric training ground for medical students, interns, resident physicians, and student nurses from affiliated schools of nursing. Board minutes explain that “election to the staff automatically elects members to the teaching faculty of the Medical School and these men rank as Professors, Associate Professors, Assistants and Demonstrators.”

The cornerstone of the new building including a time capsule was laid on October 18, 1925, and the move into the new structure took place on November 1, 1926. With the new beginning, Children’s became the first member of the Medical Center on the campus of the University of Pittsburgh. The hospital became the center for pediatric and orthopaedic training at Pitt. Its wards and clinics became the pediatric training ground for medical students, interns, resident physicians, and student nurses from affiliated schools of nursing. Board minutes explain that “election to the staff automatically elects members to the teaching faculty of the Medical School and these men rank as Professors, Associate Professors, Assistants and Demonstrators.”